Cutting Cone with Cone: An Alternative Way to Understand Conic Section

A conic section is already a great tool that helps us understand a quadratic equation visually. However, one might wonder: why bother cutting a double cone (a cone with two nappes) with a plane in the first place? Well, maybe we have to ask mathematicians from two thousand years ago. Nevertheless, let us explore an alternative method for constructing those curves that might help us understand them not only visually, but also intuitively.

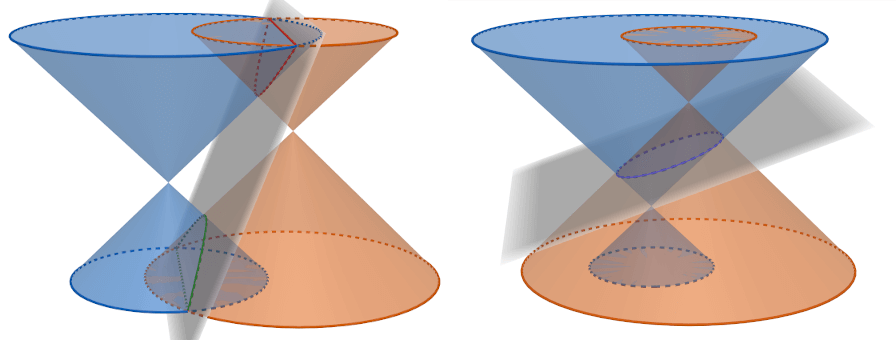

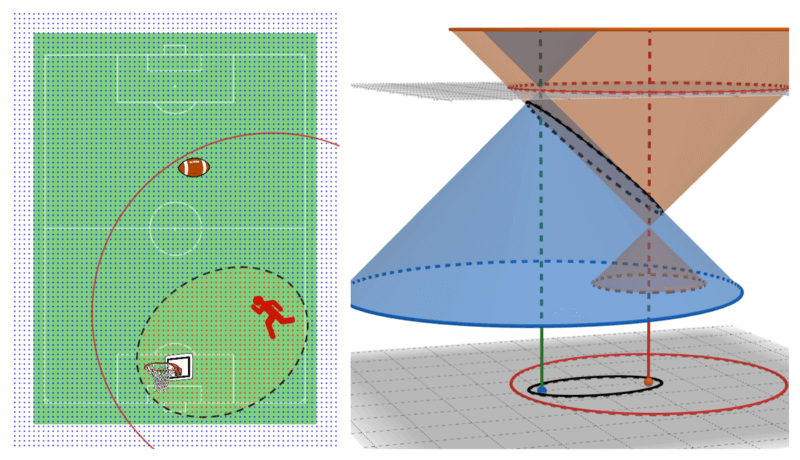

Cutting a blue cone with a grey plane is as same as cutting it with another cone in orange

An alternative proposed method is to replace the cutting plane with another identical double cone. Yes, we’re gonna cut a cone with a cone! The rules are that we can translate both cones in any direction in 3D space. On the other hand, rotation is prohibited. We might have a hard time imagining the resulted cut at first, but we are in the computer age now; so plotting them shouldn’t be too hard (try it interactively!). Also, we can observed that the cut lies on a (tilted) 2D plane, which is the same as the original cutting plane method (see proofs in the appendix).

This way, those cones will resembled a light cone that Stephen Hawking often talked about, which is great when using them to explain real-world applications. From now on, we will refer to a 3D space as

A Perpendicular Line Emerged

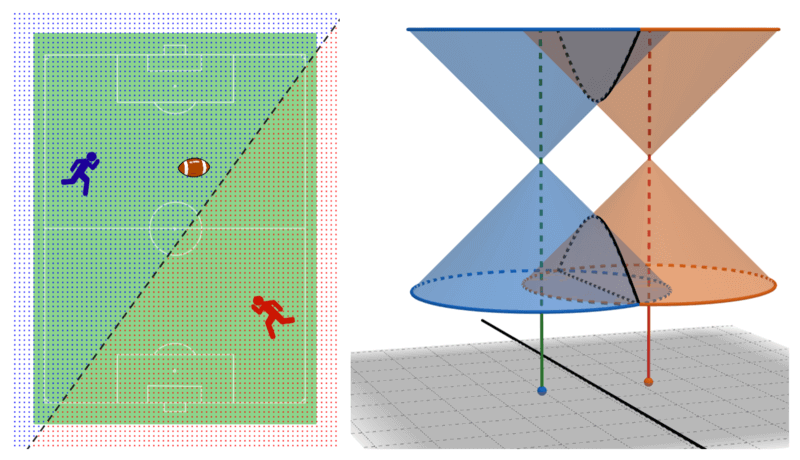

We start our first explanation with the simplest situation. Imagine a sport with two players competing in a field trying to seize a ball. Suppose that both players can move at the same speed. Given them their starting positions, then let a referee throw the ball into the field. Can we determine who can get to the ball first? Furthermore, can we determine a confident region for each player that guarantee which one of them will always gets the ball first?

This question simply asks for a Voronoi diagram with 2 seeds. We can see that if we grow a circle from each player at the same speed and stop growing parts of the border when they touched, the final border between them will become a straight perpendicular line that bisect a segment joining both players’ starting positions, which separates the result regions that tell us who wins.

Winning regions for a 2-player game, obtained by placing both apexes on the same height

To draw it in the proposed cutting cone method; we started by placing two cones with both their apexes on the same height (or at the same time on the

Hyperbola Follows Naturally

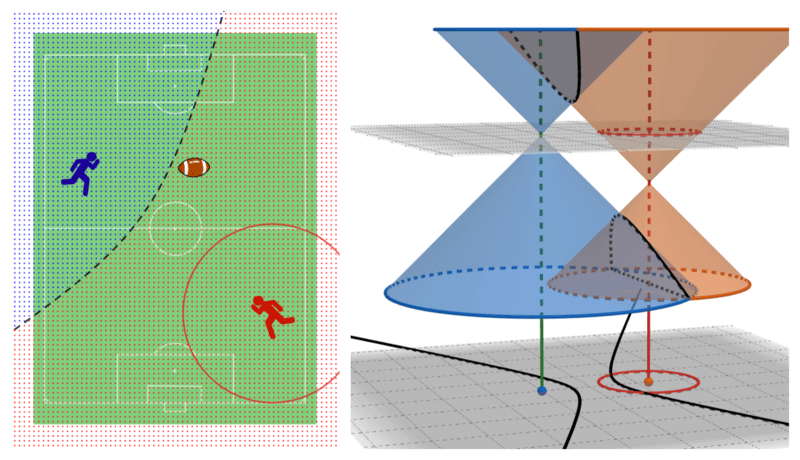

Now consider a game with the same rules as in the previous perpendicular line case. This time, however, let one player have a handicap and can start running towards the ball before another player (but they both still run at the same speed). What are the resulting regions?

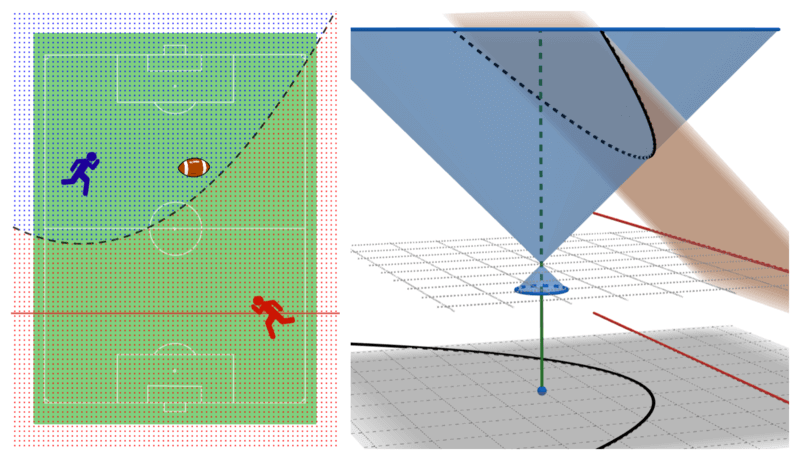

Winning regions where a blue player can move after a red player move pass that red circle

This is the most intriguing case that arises from using the cutting cone method. To visualize it, we placed their apexes on a different height (time). Also, make sure that the apex doesn’t get contained by another cone. We can see that the resulting cut lies on a tilted plane that cut both nappes, which means it must be a hyperbola! Projecting this cut onto the

Note that the hyperbola cut has two disjointed curves, but in real-world situations, we are often interested in only one branch of the curve.

Ellipse Needs a Difference Narration

The hyperbola case said that when constructing cones, their apexes can’t be contained in another cone. But what if it is contained? Well, we get an ellipse from this cut!

However, it is hard to wrap our head around the situation when one cone pointing towards the future and another cone towards the past. The 2-player game’s explanation won’t make sense anymore. Hence, we need a brand new explanation for this case.

A winning region for a red player that can run straight furthest to a red circle

Imagine a sport with only one player, to win this game they have to retrieve a ball first, then run to a goal within a time limit. Notice that the time limit can be view as a circle from their starting position with a radius equals to the furthest distance they can go. We know a starting position of the player, a position of the goal, and how much time they have. What is the winning region that the player can fetch the ball and score a goal in time?

The answer is an ellipse that can be constructed as described above. The projected ellipse on

Parabola Missing the Party

The weird thing about this case is that a parabola only has one focus (all the others have two foci). So, it is not constructible with the proposed cutting cone method. Unless we tweak this case to having two foci, where another focus is infinitely far away in both space and time. So that infinite distant cone will become a plane that is parallel to some rays in the nappes of the main cone and makes a parabolic cut.

Winning regions where a red player can choose any starting position on a red line

Trying to explain them in real-world situations with an infinity value is weird. Luckily, we can reuse the existing explanation, tweaked some rules, and it explained somewhat sensibly. Look back at the 2-player game from the perpendicular line case, we let one player has a handicap so they can choose any starting position on a straight line. Just this and now we have regions separated by a parabola.

It’s a Complement, Not a Replacement

We can see that this cutting cone method makes a lot more sense than the original cutting plane method. Though in some cases we have to work around for explanations, we gotta admit that the hyperbola case shines brightly in this explanation, which is wonderful since we are often familiar with only a circle, an ellipse, and a parabola.

There is also another special case that’s been left out. It is when one apex lies exactly on another nappe. The resulting cut will be an infinite line passing through their foci, which doesn’t agree with the degenerated case for an ellipse explanation that gives a line segment joining their foci as a result.

Keep in mind that the method has many restrictions; such as we can’t rotate cones and their slopes must be the same. These settings fit the space-time explanation well, but what if we can rotate them, or allow their slopes to have different values? It’s easy to see that the cut will not lie on a plane anymore. And also the projection will go haywire. These might be fun to analyze, but will be harder by a magnitude too.

Appendix

Notation: A sphere

Lemma 1: Given two distinct spheres

Proof: Let

Consider another distinct set of intersecting points

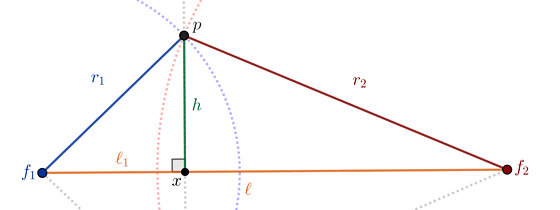

Figure 1: A cross-section of two intersected spheres with both foci

Refers to fig. 1, let

Ignore

Lemma 2: Given two distinct spheres

Proof: Let

Lemma 3: Given two distinct spheres

Proof: In the same manner of lemma 2, but change

Theorem 4: Given two distinct cones

Proof: Split into 2 cases

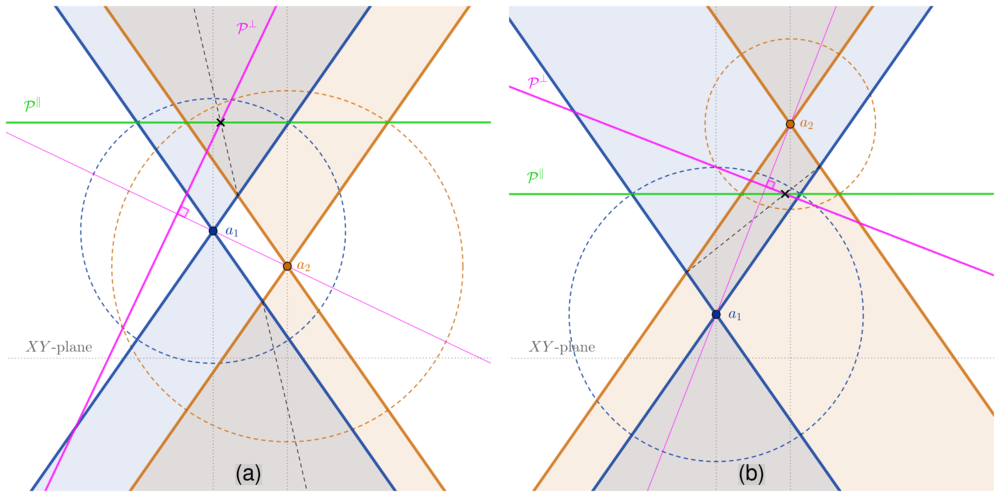

Figure 2: A cross-section that contains both apexes and parallel to

-axis

The first case, refers to fig. 2a, is when one cone does not contain another apex. Let

To find other intersect point of these cones at time

If

Another case as shown in fig. 2b, is when one cone contains another apex. Let

Other intersect point at time

author